History of linen manufacturIng in district

History of linen manufacturIng in district

8 March 2023

THE Rowallane and Slieve Croob Community Twinning Group will explore Co Down’s linen heritage in the Dan Rice Hall, Drumaness, next Wednesday, March 15.

A fully-illustrated talk will describe linen manufacturing in Down from the 1780s to the 1960s.

It will refer to mill activity at Drumaness, at Dodd’s Mill Dromara, Silcock’s Mill at Raleagh, Harris’ water mill in Ballynahinch, Magheraknock Mill, and Ballynahinch Windmill.

The event is generously funded by Newry, Mourne and Down Council. Horace Reid has done the historical research, and Francis McLean will give presentation, beginning at 4pm.

We are fortunate that we have available to us a full set of high quality prints, depicting every stage of linen manufacture in Co Down, executed by William Hincks in 1783. These often feature buildings still familiar to us, such as Scarva House, Banbridge Market House, or Linen Hill in Katesbridge (once host to Wolfe Tone, back in 1792).

One remarkable print, dedicated to Lord Moira of Montalto, and executed locally, presumably in Ballynahinch, shows a domestic interior with four women all busy spinning linen thread. Flax provided an income stream which floated all boats.

The menfolk profited from pulling and retting the beets in the fields. The womenfolk were kept busy indoors on government-subsidised spinning wheels.

All of the women were dressed in the height of fashion – lace bonnets tied with silk ribbons, quilted petticoats, revealing necklines, and Cuban-heeled shoes.

The evident prosperity in this household was common, but not exceptional. John Moore Johnston, Lord Moira’s

resident estate manager, confirmed that at fairs in Ballynahinch in the 1790s “the young women are decked out, equal to ladies of the first rank”.

Factories

In the 1700s linen spinning and weaving were skilled manual occupations, and home-based. But in the 1800s

these activities became mechanised and factory-based — and productivity soared.

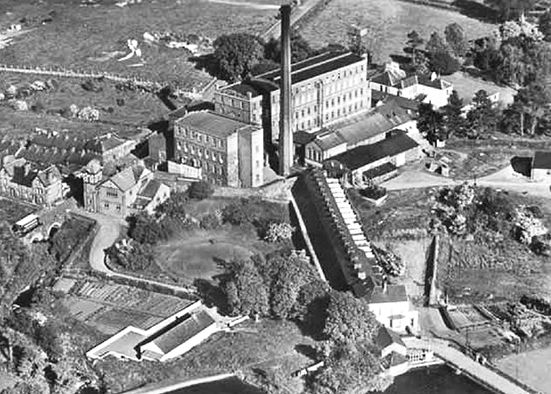

In 1850 James Hurst of Manchester opened a new mill in Drumaness, using the wet spinning process. Drumaness mill loaded linen thread on reels, which were then sold to their weaving industrial counterparts.

Wet spinning enabled flax to be spun to a finer gauge, but the process required enormous amounts of water. Drumaness has a large tank atop the mill and a full dam outside, but that was not enough. The mill actually drew most of its water from McAulay’s Lough, two miles away on the Dunmore

Road outside Spa. It was this body of water that made factories like Drumaness viable.

Flexible management

Hurst’s management team at Drumaness was diverse and flexible. It included Charlie Ward, farm manager, Davis Hunter, foreman mechanic, and Johnny

Boyd, athletics coach for the mill’s resident team of Harriers.

As well as having sustained a vital war industry, Jim Harte was a captain in the Home Guard. Ernest Sandford was a promising young man who joined as a management trainee in 1948. He had shown early initiative when in 1943 he sank an Italian destroyer – using a British Army landing craft as an attack platform. By the 1960s he was Major commanding ‘A’ Company, 3 UDR at Carryduff. In 1988 he was appointed Her Majesty’s Deputy Lieutenant of County Down.

Workers

Linen industry employees seemed content with their incomes in the 1700s. In the 1900s at Drumaness the situation was evidently the same. Peter McAvoy was pleased with £2/2/6 per fortnight. Another worker, a veteran of 61 years’ employment, began work aged 10. Employed as a rover, spreader, and drawer, she earned 7/6 per fortnight. She went full time at age 11 and was delighted when her wages then more than doubled to 16/6.

WW2 bombers

During World War Two Ulster linen became a vital wartime industry. Battling shortages, the aircraft industry turned to alternative materials. The revolutionary Mosquito bomber was built of plywood, skinned with a composite cotton fabric.

The twin-engine Wellington, a mainstay of Bomber Command, was entirely skinned with Irish linen, reinforced with dope. 11,461 Wellington aircraft were built during the course of the war. That’s an awful lot of Irish linen production.

Linen hi-tech

However, the war had cut off one of the main sources of flax supply in continental Belgium. This led to an emergency expansion of flax growing in Ulster.

One Belgian industrialist, Jules Bevernage, brought a new technology to Dromara when he fled the Nazis. In 1940 the Flax Development Committee inspected his new accelerated retting process at Dodd’s Mill.

Flax beets were boiled, instead of being steeped in lintholes. This allowed retting and scutching to continue all year round. The process could be self-sustaining, because “shous”, the husk by-product of scutching, made excellent fuel.

Competition

But the good times were not to last. Terylene was patented in 1941 and then marketed by ICI. A flood of synthetic fabrics followed. While in many ways a superior product, flax required much labour-intensive skilled processing, and could no longer compete. The linen industry in Ulster was eventually reduced to a niche luxury market.

Orders for linen yarn fell off, and Drumaness Mill closed in 1968. The tall mill chimney was toppled in 1985, soon to be followed by the rest of the complex.

These and many other stories will be told in the Dan Rice Hall in Drumaness next Wednesday at 4pm. Tea and coffee are on offer. All are welcome.